Nouchimiich Eeyou Eetouin Ehwaptakoonoouch

Reading the signs

The Cree traditional way of life and knowledge acquisition are based on land occupancy, reading natural signs and experience-sharing. The Board’s monitoring framework adopts this philosophy and makes use of the advantage of having access to the territory’s main occupants.

In practicing their traditional activities, the Crees are best-placed to note the effectiveness of the provisions designed to better harmonize forestry-related activities with their way of life. Their involvement in the participative mechanisms provided for in the Paix des Braves Agreement also promotes experience-sharing in this regard.

The Board proposes a monitoring framework designed to bring together the different signs enabling ongoing assessment of whether the objectives of the Adapted Forestry Regime are being achieved. To do so, it relies extensively on the appreciation of the territory’s occupants and the stakeholders involved in implementing the Paix des Braves Agreement.

Bases of the monitoring framework

Board Responsibilities

The Cree-Québec Forestry Board (CQFB) has the responsibility to monitor, analyze and assess the implementation of the forestry provisions of the Agreement concerning a new relationship between the Gouvernement du Québec and the Crees of Québec (ANRQC).[1]

This assessment must enable the Board to recommend, to the parties, adjustments or modifications required for the Adapted Forestry Regime applicable to Agreement territory to evolve in keeping with an approach of continuous improvement.[2]

At the same time, the Board is also responsible for monitoring the implementation mechanisms for the Joint Working Groups (JWG) and is involved in reviewing the forest management plans.[3]

Context

After signing the Agreement, in 2002, the parties began implementing the Adapted Forestry Regime through transitional measures in the early years, up to the completion of the first full planning cycle between 2008 and 2013.

The Cree-Québec Forestry Board’s initial monitoring-related concerns were primarily to ensure that all of Chapter 3’s forestry-related provisions were gradually implemented in a spirit of collaboration between all stakeholders.

In 2009, the Board produced a first assessment of the implementation of the Agreement’s forestry-related provisions for the period 2002-2008.

At this time, the Board observed that the Ministère des Ressources naturelles du Québec (MRN) was deploying measures to ensure implementation of the great majority of Chapter 3’s technical provisions. However, it was recommended that JWG members’ intervention capacity be strengthened so that they could contribute to this process in keeping with their mandate.

The Board also observed that none of the stakeholders was measuring the extent to which Agreement objectives had been reached or questioning the propensity of the Adapted Forestry Regime’s provisions to promote the objectives’ achievement.

As a result, the Board identified implementation monitoring of the Agreement as a priority issue and made the desire to implement the tools and measures required for up-to-date information on achievement of the Agreement’s objectives and provisions one of its action priorities.

In recent years, the Board has developed its monitoring framework and agreed on an action plan to achieve the implementation of the monitoring program.

[1] ANRQC, section 3.30 a)

[2] ANRQC, section 3.30 b) et 3.6

[3] ANRQC, sections 3.30 d) e) f)

Preferred approach

A simple tool meeting the Board’s needs

The monitoring framework is, first and foremost, for Board members’ use to enable them to advise the parties on the Adapted Forestry Regime’s evolution. the Board has been careful to restrict itself to its mandate, which concerns exclusively Chapter 3 (Forestry) of the Paix des Braves. The framework concept is also flexible and able to evolve, in the sense that it is not intended to try to include every possible element from the outset.

Objectives and criteria

The monitoring framework is based on the objectives stated in the very first section of Chapter 3 (Forestry):

«The Québec forestry regime will apply in the Territory in a manner that allows:

- adaptations to better take into account the Cree traditional way of life;

- greater integration of concerns relating to sustainable development;

- participation, in the form of consultation, by the James Bay Crees in the various forest activities operations planning and management processes. »[4]

- collaboration in the form of concerted action, between the Cree Nation Government (CNG) and the Eeyou Istchee James Bay Regional Government (EIJBRG) in the planning process set out in appendix C-4 of the current Agreement.

The framework expresses each of these objectives as a series of criteria. These criteria increase the angles from which an objective is studied and constitute the basis for determining whether an objective has been attained. Therefore, each objective has a number of facets and is described according to several criteria.

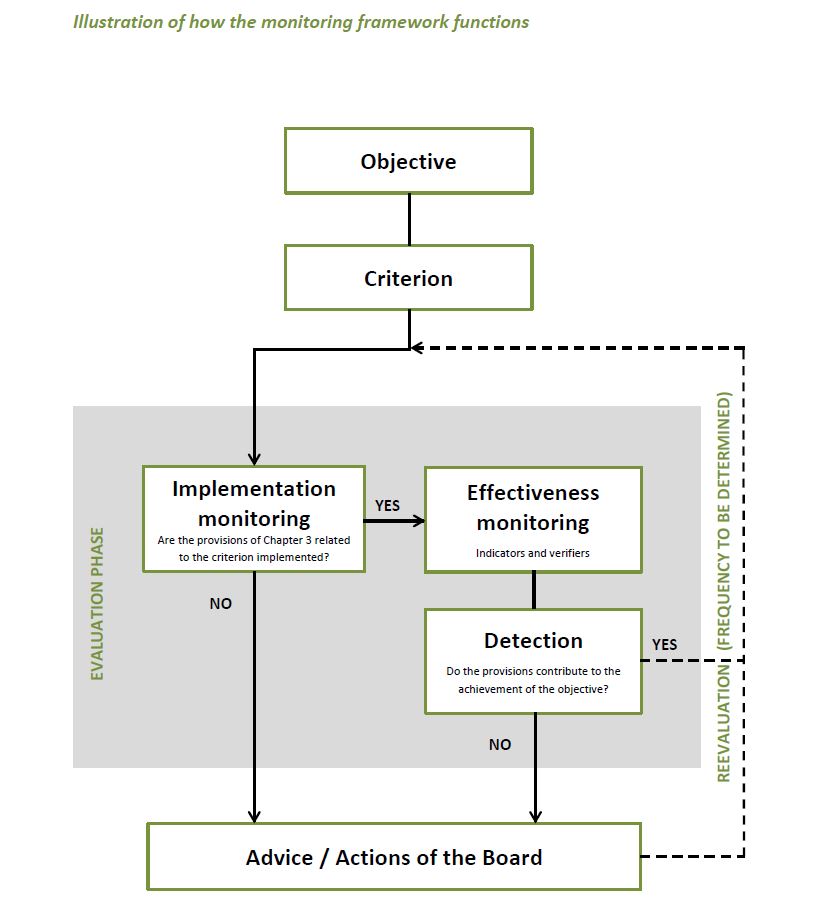

Once the “objectives and criteria” structure has been established, the Board enters into the evaluative portion of the monitoring framework. This entails monitoring the provisions’ application in order to systematically paint a picture of the implementation process.

The Board monitors the effectiveness of the criteria whose associated provisions have been implemented to determine whether their implementation contributes to achieving the objectives of Chapter 3. In other words, the Board wants to know whether the provisions are doing the job.

[4] ANRQC, section 3.1

Detection-based assessment

The Board’s monitoring framework differs from the usual criteria and indicator frameworks in that it is not based primarily on achievement of objectives. It is more of a tool for detecting what works well and not so well in the Adapted Forestry Regime’s implementation.

The assessment counts heavily on stakeholder involvement and stakeholder evaluation of whether the provisions of Chapter 3 allow the objectives to be reached.

Concrete action

Through its monitoring framework, the Board seeks to be proactive and to propose concrete action for any problem that may be detected. The Board could also implement further monitoring designed to get more information on the nature of the problems detected or to launch initiatives aimed at rectification.

The monitoring framework is a complementary tool to the Board’s strategic planning in that it may influence the Board’s directions and action priorities depending on the results obtained along the way. Similarly, through its directions and choice of files of interest, the Board may prioritize certain monitoring framework elements and focus assessments on certain criteria or more specific indicators.

Objective 1: Traditional Way of Life

Adaptations to better take into account the Cree traditional way of life

The Agreement specifies that the Cree Nation must continue to benefit from its rich cultural heritage, its language and its traditional way of life in a context of growing modernization (s. 2.2). Chapter 3 deals with forestry and seeks to have the Québec forest regime apply on Agreement territory in a manner that allows adaptations to better take into account the Cree traditional way of life.

To assess to what extent this objective has been attained, the Board seeksto better understand the “traditional way of life” concept. In this regard, the Cree Trappers Association proposes a definition of the concept that allows us to understand its scope and that illustrates its multidimensional aspect as well as the difficulty of circumscribing it:

Eeyou define Eeyou culture simply as the way of life adopted by Eeyou. In fact, Eeyou describe Eeyou culture as “Eeyou Pimaatisiiwin” or Eeyou way of life. For Eeyou, culture is determined and shaped by Eeyou Iyihtiwin – the Eeyou way of doing things – and encompasses the complex whole of beliefs, values, principles, practices, institutions, attitudes, morals, customs, traditions and knowledge of Eeyou. These elements influence the determination of Eeyou laws.

The Board adopts the cultural dimension of this explanation, that is, that the Crees’ traditional activities, regardless of the intensity with which they are practiced and the evolution of the tools used, represent a vector for transmitting culture and language and that the conditions found in the forest must allow these activities to be carried out. However, a great many factors other than forest conditions can also influence the Crees’ practice of the traditional way of life.

To effectively measure the extent to which this objective is attained, the Board is focussing on the adaptations included in Chapter 3 with regard to the Québec forest regime and trying to understand whether these adaptations contribute positively to taking into account the traditional way of life. Given the scope of the concept, the Board considers that it is the Crees who are skilled in practicing and teaching the traditional way of life who are able to judge whether the adaptations to Chapter 3 are beneficial.

In this regard, the most relevant criteria to observe in the context of the monitoring framework are the main categories of adaptations found in Chapter 3. These adaptations, which represent a different way of perceiving forest management compared to the Québec regime, must support the Crees in practicing their traditional way of life.

CRITERION 1.1: ZONING

Under the Québec forest regime, the territory is defined in territorial reference units (TRU) and management units (MU) according to biophysical, ecological and socio-economic parameters. In Chapter 3, adaptations are provided for to adjust the TRUs and MUs to the geographical boundaries of traplines and the reality of Cree communities. This zoning is designed to ensure that forest conditions are suitable to allow practice of the traditional way of life in all traplines at all times.

Related provisions

3.7 The trapline defined as the territorial reference unit

3.8 Management units and northern limit

CRITERION 1.2: SITES OF SPECIAL INTEREST TO THE CREE

Cultural sites are venues that are suitable for transmitting knowledge, culture, language and values through the activities carried out there. They also make it possible to maintain the notion of identity based on land occupancy. Cultural sites can include campsites and the area around them, sacred sites, burial grounds, gathering sites, archaeological sites, portage trails, bear dens, blinds, water sources, etc. Further, forest activities must be harmonized with the Crees’ hunting, fishing and trapping activities. To do so, forest management must take wildlife habitat protection into account and ensure that quality wildlife habitats are maintained on all of the territory’s traplines. The adapted forestry regime stipulates that the tallymen must identify cultural sites and forested areas presenting wildlife interest for which special protection measures are prescribed.

Related provisions

| 3.9 Sites of special interest (1 %) 3.10 Sites of special wildlife interest (25 %) |

C-4 18. Planning-support maps 3.71-3.73 Firewood |

CRITERION 1.3: MANAGEMENT APPROACH

Under the Québec forest regime, the sylvicultural approaches selected for forest management depend on a range of variants such as forest composition, stand structure, forest regeneration processes, soil types, effects on landscape, socio-economic factors, etc. Chapter 3’s management approach is adapted to the Agreement’s particular context, considering the variants listed above but advocating increased acceptability and prescribing specific thresholds to comply with in terms of cutting areas, residual stands to preserve, the annual allowable cut rate, the acceptable level of disturbance by trapline, maintenance of the hardwood component, timber recovery in case of a natural disaster, etc. The management approach promoted under the adapted forestry regime is aimed at ensuring that the Crees can continue to practice their traditional activities in harmony with forest management in the territory.

Related provisions

| 3.11 Maintaining forest cover 3.14 Disturbances of natural or anthropogenic origin C-2 Mosaic cutting, size of harvest blocks, height of residual stands |

C3 Maintenance of forest cover, mixed stand strategy, wildlife habitat guidelines C-4 Harmonization measures C-5 Special recovery plans for wood affected by natural disturbances |

CRITERION 1.4: RIPARIAN AREAS

Under the Québec forest regime, riparian zones enjoy special protection during forest management activities primarily for hydrographic reasons, that is, to avoid sediment inputs into streams and preserve aquatic environment quality. The Crees associate other essential functions linked to practicing their way of life with riparian environments. For example, their richness of wildlife habitats makes it possible to concentrate various hunting and trapping activities there. Many temporary camps and other cultural sites are also concentrated there. The adapted forestry regime provides for additional protective measures.

Related provisions

| 3.12 Protection of forests adjacent to watercourses and lakes 3.13 Mechanisms for biological refuges |

CRITERION 1.5: ACCESS

Forest activities involve building and maintaining a major road network in the territory. The Crees can take advantage of this network to access the territory and to travel between various sites. The same road network also gives access to vacationers and other users of the territory, thereby potentially increasing hunting, fishing and trapping activity. Access management, therefore, has direct and indirect impacts on the practice of traditional activities. Chapter 3 provides for adaptations to the Québec forest regime by giving tallymen increased influence on road network development.

Related provisions

| 3.15 Development of the road access network 3.10.6 Limit the establishment of major access roads within the 25% |

INDICATORS AND VERIFIERS

The indicators selected to evaluate criteria 1.1 to 1.5 are grouped.

Given the specific theme of the Cree way of life, the Board relies on two qualitative indicators, taking advantage of the land users’ knowledge. They are best placed to determine if the adaptations to the Québec Forest Regime promote better taking into acount the traditional way of life.

The proposed indicators are:

- Tallyman (and members of his family)’s appreciation of its ability to practice and teach the Cree traditional way of life

- Tallyman (and members of his family)’s appreciation of Chapter 3 provisions/adaptations and their usefulness in taking into account the Cree way of life

The Board will assess the possibility of adding one or more quantitative indicators after reviewing the data collected by the Cree Trappers Association and the other related organizations more closely. In this case, adding quantitative indicators is advisable, but not mandatory. Data should be reliable and meaningful for our context before anything else.

The proposed main verifiers are:

- JWG reports (format to be reviewed – frequency TBD)

- JWG minutes of consultation meetings

- CQFB interviews with tallymen and families (frequency 5 years)

Other options are also possible:

- Cree land monitors

- Pilot traplines / families

- Focus groups

- CTA general assemblies

- Other specific events or workshops

- Caribou plan sections for roads and access

Objective 2: Sustainable Development

Aim for greater integration of concerns relating to sustainable development

In the Agreement, both the Cree nation and the Québec nation agree to continue the development of Northern Québec (s. 2.1). Where forestry is concerned, the Agreement provides a framework for this development, specifying that the forestry regime applicable on the territory must allow greater integration of concerns relating to sustainable development.

The Brundtland Commission defined sustainable development as: “development which meets the needs of current generations without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs”.[1] Similarly, the Indigenous peoples’ perspective is often expressed in terms of responsibility to the seventh generation:

We cannot simply think of our survival; each new generation is responsible to ensure the survival of the seventh generation. The prophecy given to us, tells us that what we do today will affect the seventh generation and because of this we must bear in mind our responsibility to them today and always. [2]

The Board’s challenge is to propose a way to express the concept of sustainable development so that the actions taken today can be evaluated in terms of their potential impact on future generations. The Board seeks a fair balance between the three sustainable development axes (economic, social and environmental) and fairness to both the Crees and Quebeckers (Jamesians) living in the territory, now and in the future.

The key is to identify sustainable development-related concerns that reflect the three axes and represent criteria on which implementation of the Agreement’s adapted forestry regime could have an impact. The Board proposes assessing whether Chapter 3 of the Agreement and its adapted forestry regime contribute to sustainable development through these criteria.

A participatory exercise enabled us to agree on the most relevant criteria to assess in the monitoring framework. These criteria are aspects that are not already covered by objectives 1 and 3, which also represent concerns relating to sustainable development.

[1] United Nations. 1987. Our Common Future. Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development.

[2] Clarkson, Linda, Vern Morrissette and Gabriel Regallet. 1992. Our Responsibility to the Seventh Generation. International Institute for Sustainable Development.

Economic axis

CRITERION 2.1: COMMUNITIES’ ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT

The Agreement has a self-professed goal of making the Cree Nation increasingly responsible for its economic development. Through the Agreement, Québec agrees to encourage and facilitate the Crees’ participation in forest-related development projects. The economic forest-related development resulting from the Agreement’s implementation can take the form of income-sharing (indexation formula including timber royalties), guaranteed volumes, business partnerships (community or individual) and contracts of all sorts (timber allowance, work performance, etc.).

Related provisions

| 3.63 Access to forest resources 3.64-3.65 Employment and contracts |

Chapter 7 – Financial provisions 3.66-3.70 Cree-Québec Forest Economics Council (CQFEC) |

CRITERION 2.2: JOB CREATION AND MAINTENANCE

With a relatively high unemployment rate and a markedly growing active population, the Crees identify the forest sector as a potentially important source of job creation. They are looking for sustainable, quality jobs and the support required to develop the skills needed to hold them. Job creation must not simply constitute a transfer or occur to the detriment of Jamesian workers. Maintaining existing jobs is also an important factor. It is hoped that the entire regional population can obtain equivalent opportunities with regard to jobs in the forest sector.

Related provisions

| 3.60-3.63 Access to forest resources 3.64-3.65 Employment and contracts |

3.74 Agreements with forestry enterprise 3.66-3.70 Cree-Québec Forest Economics Council (CQFEC) |

CRITERION 2.3: FOREST SECTOR VIABILITY IN THE REGION

The forest sector’s viability can be influenced by a great many contextual or structural factors, be it on the regional, national or international scale. The Agreement’s adapted forestry regime is, however, a specific factor that makes the Northern Québec region unique. Therefore, it is important to verify whether the requirements related to Chapter 3 become constraints reducing the regional forest sector’s viability vis-à-vis other Québec regions, while being mindful of the territory’s unique commitment and rigor to achieving sustainable development.

Related provisions

Spirit of the Agreement (Chapter 2)

3.66-3.70 Cree-Québec Forest Economics Council (CQFEC)

INDICATORS AND VERIFIERS

The indicators and verifiers proposed for the economic criteria have been developped in partnership with economists from the Bureau de mise en marché des bois (BMMB):

Indicators for criterion 2.1

- Number of Cree businesses

- Proportion of Cree businesses compared to the rest of Quebec businesses

- Hectares treated / volumes harvested or processed by Cree businesses

- Proportion of hectares treated / volumes harvested or processed by the rest of Quebec businesses

Verifiers

- MRN Business directory

- Mills registry (Industria)

- CQFEC recommendations to the parties

- CQFEC minutes, actions and achievements

Indicators for criterion 2.2

- Number of Cree workers in the forest sector

- Employment ratio Cree / total employment in the forest sector

- CQFEC contributions to provisions 3.64-3.70

Verifiers

- Community surveys (responsibility and frequency to be determined)

- Statistics Canada surveys

- Companies forestry intervention report

- CQFEC minutes, actions and achievements

- Report of the wood marketing board (BMMB)

Indicators for criterion 2.3

- Volume harvested in Chapter 3 management units (MUs)

- Ratio of volume harvested in Chapter 3 MUs / total volume harvested in Quebec

- Royalties paid for Chapter 3 MUs

- Ratio of royalties paid for Chapter 3 MUs / total royalties paid in Quebec

- Ratio of AAC for Chapter 3 MUs / total Quebec AAC

- Evolution in operating costs for Chapter 3 MUs

- CQFEC contribution regarding the utilization of volume guaranteed to the Crees (article 3.60)

Verifiers

- MRN measurement and billing data (MesuBois)

- Office of the Chief Forester

- Pricing models BMMB

- BMMB reports and surveys (Chapter 3 territory)

- CQFEC recommendations to the parties

Social axis

CRITERION 2.4: CONSIDERING THE NEEDS OF ALL LAND USERS

The Crees are currently experiencing significant demographic growth, which increases the number of people using the territory and could put more pressure on resources. While Chapter 3 of the Agreement focuses mainly on strategies at the trapline level and on the tallymen’s participation in forest planning activities, the approach advocated by the Agreement must be fair and representative for all groups of Cree users, young and old, men and women, seasonal hunters and full-time trappers, with or without access to a family hunting ground. Further, this approach strives to avoid not adversely affect vacationers or non-Cree hunters, who also wish to take advantage of the territory’s resources.

Related provisions

3.4 Improved harmonization of forest activities with hunting, fishing and trapping activities

Spirit of the Agreement (Chapter 2)

INDICATORS AND VERIFIERS

The Board suggests two qualitative indicators to assess the appreciation of the actors targeted by criterion 2.4:

- Appreciation of Cree land users, other than tallymen, of their ability to practice the Cree way of life, their access to the land and their level of participation in land management decisions

- Jamésiens’ (non Cree) appreciation of their access to the land and of level of participation in land management decisions

The proposed verifiers (sources and potential data collection tools) vary:

- Data from the Cree Trappers’ Association

- CQFB interviews with other users of the land and community members (frequency > 5 years)

- TGIRT reports (if available)

- Income Security Program / Board

- Others (i.e. Cree Culture Department, COTA, Regional wildlife table, outfitters, joint committee for hunting, fishing, trapping, etc.)

Environmental axis

CRITERION 2.5: BIODIVERSITY PROTECTION

Protecting biodiversity is clearly an element that is assessed globally on the national and international scale through various types of monitoring. Using a more specific objective, we will look at validating the management strategy used throughout the Agreement’s adapted forestry regime to ensure that it maintains the ecological functions associated with the diversity of the ecosystems representative of the territory. Similarly, the impact of the adapted forestry regime’s management strategy must also be evaluated vis-à-vis species designated threatened or vulnerable and protected wildlife habitats.

Related provisions

C-2 Mosaic cutting, size of harvest blocks, height of residual stands

C-3 Maintenance of forest cover, mixed stnd strategy, wildlife habitat guidelines

3.10 Sites of special wildlife interest (25%)

CRITERION 2.6: INTEGRITY OF KEY SOCIOECOLOGICAL ECOSYSTEMS

The concept of key socioecological ecosystems is associated with the concept of ecosystem-based services, i.e. the benefits that humans derive from certain ecosystems. In the case at hand, these ecosystems are most often linked to Cree traditional activities. For example, the cultural importance attributed to mature mixed forest stands as crucial moose wildlife habitats, to white spruce forest stands as an important source of medicinal plants, to spawning grounds and to many other ecosystems. Because these ecosystems are often under-represented in the territory, it is important to identify them and verify whether the management strategy used in the territory ensures their integrity.

Related provisions

| C-3 Mixed Stands Strategy 3.7 The trapline defined as the territorial reference unit 3.10 Sites of special wildlife interest (25%) 3.11 Maintaining forest cover + Schedule C-2 3.12 Protection of forests adjacent to watercourses and lakes |

C-3 Directive for wildlife habitats C-4 18. Planning-support maps 3.13 C-4 –Biological refuges 3.15.3 C-4 18 – Roads vs spawning grounds |

CRITERION 2.7: KNOWLEDGE ABOUT THE TERRITORY

Developing better knowledge of the territory’s forest ecosystems, their components in general and wildlife in particular must promote the development of management strategies that are more respectful of natural dynamics and that help ensure resource sustainability. Effective implementation of the adapted forestry regime is based on the existence of knowledge acquisition programs that can take different forms and target different goals such as maintenance, transfer, sharing and research, and which will help develop strategies and/or mechanisms designed to put Cree traditional knowledge to good use in the territory.

Related provisions

| 3.6 The forestry regime will evolve Cree-Québec Forestry Board Joint Working Groups and coordinators |

C-4 18. Planning support maps C-4 Section on monitoring |

INDICATORS AND VERIFIERS

The proposed indicators for criteria 2.5 and 2.6 have been discussed with professionnals from MFFP and MDDELCC. The Board proposes using mainly indicators already monitored by the two entities to facilitate monitoring:

- VOIT Charts – values, objectives, indicators and targets (Biophysical indicators measured regionally)

- Sensitive wildlife species (black spruce forests)

Woodland caribou

Marten

- Wildlife species of socio-economic interest

Moose

Brook Trout - Protected sensitive sites under the regulation respecting the sustainable development of forests (RRSDF)

- Effective protection of forest adjacent to watercourses following the relocation of biological refuges

- VOIT presented by the Crees

The verifiers associated with these indicators are multiple and remain to be clarified:

- Status of vulnerable / threatened species

- MFFP monitoring

- MDDELCC monitoring

- CTA data

- Sensitive location raised by the tallymen and integrated into the MFFP’s geo-referenced database

Other options:

- Habitat suitability models

- FSC monitoring

- Other monitoring initiatives & results

- Experimental sites

- Inventories

- Research initiatives & results

- Monitoring accorded to VOIT

More specific indicators are proposed for criterion 2.7 on the body of knowledge. Most cases involve compiling / keeping track of the initiatives:

- Land visits

- Initiatives for documenting knowledge

- Land use studies

- Inventories

- Workshops/Symposiums/Conferences

- Publications

These initiatives will be compiled by the Board Secretariat.

Objective 3 Participation

Ensure participation, in the form of consultation, by the Crees in the various forest activities operations planning and management processes

The concept of consultation of Native peoples translates differently depending on the context. Using a more overall approach, for example, the Québec government’s guide for consulting Native peoples[1] and the protocol of the First Nations of Québec and Labrador Sustainable Development Institute[2] take an angle based on the Crown’s legal obligation to consult and accommodate. The environmental and social protection regime of the James Bay and Northern Québec Agreement provides for a special status and involvement for the Cree people to protect their rights and guarantees. Further, many specific forest management frameworks, such as sustainable forest development principles and forest certification standards, define expectations regarding Native consultation and participation even more clearly.

In the Agreement, the Crees and Québec agree on various forums involving different players to ensure the Crees’ participation in the implementation of the adapted forestry regime. They also agree on specific processes for forest management plan elaboration, consultation and monitoring. The Agreement introduces the notions of real and significant participation in forest management activities, of taking into account wildlife habitat protection and of dispute resolution between users, through the creation of joint working groups.

Chapter 3 of the Agreement seeks to ensure that various consultation mechanisms ensure the Crees’ real and significant participation in the different forest activities operations planning and management processes. The Board seeks to evaluate the effectiveness of these consultation mechanisms in promoting the participation of the Crees.

To do so, the Board sought to look more closely at the concept of Cree participation to better understand their aspirations in this regard. Our findings show that the Crees have a multidimensional approach to participation. They clearly hope to have a concrete influence on the result of the process, as much as the process itself is adapted so as to respect and value their culture and promote their development and greater autonomy as a nation.

This led the Board to conduct a participatory exercise to identify the most significant criteria allowing consultation mechanism effectiveness with respect to the Crees’ participation-related aspirations to be assessed.

[1] Gouvernement du Québec. 2008. Guide intérimaire en matière de consultation des communautés autochtones. Groupe interministériel de soutien sur la consultation des Autochtones.

[2] Institut de développement durable des Premières Nations du Québec et du Labrador. 2005. Protocole de consultation des Premières Nations du Québec et du Labrador. Assemblée des Premières Nations du Québec et du Labrador.

CRITERION 3.1: EFFECTIVENESS OF MECHANISMS AND DISPUTE RESOLUTION

Participation is not an end in itself. Its main virtue is to lead to management proposals that are acceptable to all of the parties involved, ecologically appropriate and technically realistic. In this spirit, the consultation mechanisms under Chapter 3 of the Agreement must evidently show a real opportunity for the Crees to influence the process. They must also lead to concrete results so that the forest activities in the territory are not jeopardized by never-ending processes. Otherwise, participation may, on occasion, lead to divergent viewpoints and opinions that are difficult to reconcile. The dispute resolution mechanism implemented to deal with cases which have reached an impasse must be fair, equitable, efficient and satisfying.

Related provisions

| Cree-Québec Forestry Board Joint Working Groups Joint Working Groups Coordinators 3.14 Disturbance of natural or anthropogenic origin 3.15 Development of the road access network |

C-4 19-23 Conflict resolution C-4 18. Plan monitoring |

CRITERION 3.2: ACKNOWLEDGEMENT OF EENOU STEWARDSHIP OF THE LAND

Significant participation by the Crees involves mechanisms adapted to their culture. The Crees would like consultation mechanisms to recognize their ecological knowledge, acquired through experience and observation, that can be very useful for understanding the impacts of forest operations in the territory and, especially, for minimizing these impacts on hunting, fishing and trapping activities. Their participation is intended to allow the individuals that have this knowledge (tallymen or other experienced trappers) to contribute their expertise rather than having non-Crees interpret the scope of the knowledge the Crees hold. The Crees would also like consultation mechanisms to attribute value to the tallymen’s stewardship role. Traditionally, the essence of the Cree culture is based on land stewardship activities, skills and ethics. Participation must recognize tallymen’s leadership in the ways the territory is organized.

Related provisions

Joint Working Groups

C-4

3.1 c) and d) principles of participation and collaboration

3.13 Mechanisms relative to biological refuges

3.9.5 Overlap of the 1 % and biological refuges

CRITERION 3.3: CONTRIBUTION TO GOVERNANCE OF CREE INSTITUTIONS

Among the Crees, participation is seen as a way of being included in decision-making at all levels and a way of empowering community and regional institutions. The Crees have their own institutions and their own unique ways of exercising their governance. In order to promote greater autonomy on the part of the Crees, the consultation mechanisms under Chapter 3 of the Agreement must encourage Cree participation not only on the scale of the trapline but also through their institutions, whether they work at the community or nation level. These mechanisms must also give Cree institutions the opportunity of increasing their influence not only on management plans but also on other components of forest management.

Related provisions

| Cree-Québec Forestry Board Joint Working Groups |

Joint Working Groups Coordinators |

CRITERION 3.4: INDIVIDUAL AND INSTUTITIONAL CAPACITY DEVELOPMENT

Forest operations planning and management uses a range of disciplinary knowledge and requires different technical tools. While participation should promote a greater role to be played by the Crees, it is important that the individuals and institutions involved have the appropriate knowledge and technical means needed to contribute in an enlightened manner. The consultation mechanisms under Chapter 3 of the Agreement must, therefore, be adapted accordingly and structured so as to foster the development of the Crees’ individual and institutional capacities where forest management is concerned. On the other hand, forest management in the territory involves a meeting of the two cultures. Taking the Crees’ interests into account requires forest managers to be made more aware of the Cree culture. This awareness can take the form of efforts managers make to increase their insight, the Crees’ openness to sharing their culture and the availability of tools ands mechanisms designed to foster a better understanding.

Related provisions

Spirit of the Agreement (Chapter 2)

INDICATORS AND VERIFIERS

The proposed indicators for the participation criteria are:

Criteria 3.1

- JWGs & Coordinators’ appreciation

- Planners’ appreciation

- Tallymans’ appreciation

- Occurrence of conflicts

- Cree contribution to monitoring forest management plan activities

- Conflict resolution/conflict occurrence ratio

- Duration of conflicts before settlement

Criteria 3.2

- Tallyman’s appreciation of his level of influence and of the participation process (residual block location, road network development, sensitive site identification, harmonization measures, etc.)

- Appreciation of the JWG and the tallymen for Cree involvement in determining the mechanisms for the relocation of biological refuges and the areas of interest for the Crees.

Criteria 3.3

- CNG/Band councils’ appreciation

Criteria 3.4

- Existence of training programs/activities

- Number of cross-cultural awareness activities

* An indicator on Cree institutional capacity remains to be defined

For all indicators, the verifiers proposed are:

- JWG reports (format to be reviewed – frequency TBD)

- JWG minutes of consultation meetings

- Harmonization follow-up grids

- MFFP monitoring reports (CQNRA statistics updates, five-year reports, others)

- CQFB interviews/assessments (frequency 5 years)

- Table for monitoring conflicts prepared by the coordinators

- Tracking tool for MFFP requests and harmonization measures

- TGIRT reports (if available)

More specifically, for the indicator on training programs/activities, an additional verifier is proposed:

- CNG/CHRD assessment/data on training, budget, human resources, etc.

Objective 4 Collaboration

Ensure collaboration, in the form of concerted action, by the Cree Nation Government (CNG) and by the Eeyou Istchee James Bay Regional Government (EIJBRG) in the participation process for the forest planning

Following the coming into effect of the Sustainable Forest Development Act (SDFA), in 2013, changes had to be made to Chapter 3 of the Paix des Braves to harmonize the Adapted Forestry Regime (AFR) with the new Québec Forest Regime on Paix des Braves territory. This 4th objective was, therefore, added to the general provisions at the very beginning of Chapter 3 of the Paix des Braves. The objective seeks to reflect the parties’ commitments made under the Agreement on Governance in the Eeyou Istchee James Bay Territory Between the Crees of Eeyou Istchee and the Gouvernement du Québec in 2012.

This objective fits in with sustainable development movement, where natural resource and land management gradually become participative. More specifically, the Sustainable Forest Management Strategy seeks to increase Native peoples’ and local populations’ participation in forest management. There is a public participation rating scale that presupposes growing involvement of the populations concerned: information, consultation, concertation and partnership. Concertation is a higher level of participation than consultation, because users have a greater involvement in decision-making.

To implement this concertation, Chapter 3 of the Paix des Braves provides for the creation of integrated land and resource management panels (TGIRT) on Category II and III lands in AFR territory. Their mandate, as stipulated in Schedule C-4, is:

To ensure that the interests and concerns of the Cree (on Category II and III lands) and the relevant Jamésians (on Category II lands) are taken into account, to set local sustainable forest development objectives and to agree upon measures for the harmonization of uses. On Category II lands, the CNG takes concerted action with the Cree tallymen and other Cree stakeholders concerned in this respect. On Category III lands, it is the Eeyou Istchee James Bay Regional Government (GREIBJ) that takes concerted action with all the relevant Cree and Jamésian stakeholders.

To assess this objective, the Board sought to better understand the concept of collaboration in the form of concerted action, or concertation, and how the parties intend to implement it in the context of Chapter 3 of the Paix des Braves since, apart from the above-mentioned mandate, the Paix des Braves gives no details on this subject.

Collaboration is a very broad concept that presupposes working or thinking together to achieve a common objective. It is a process whereby two or more people or organizations come together to do intellectual work with common objectives.

Concertation, which is a relatively new concept in the field of natural resources management, has no real theoretical basis. Its definitions vary and do not always clearly differentiate concertation from consultation. Consequently, it seems appropriate to use the definition the Québec government provides in the glossary to the Guide sur les tables de gestion intégrée des ressources et du territoire:[1]

A planned public participation process through which actors targeted by public authorities are invited to discuss and deliberate among themselves, going beyond divergent opinions and interests, in order to reach agreement (by compromise or consensus) on a solution to be proposed to resolve a common problem and thus influence the final decision (adapted from Fortier, 2010).

This definition, taken from the recreation sector, is rather open and could give rise to interpretation. It would, therefore, be important that the Board ensure that the stakeholders have a common interpretation of the concept. The contribution of advisors from the academic community was sought to clarify things. Decision-making by compromise or consensus presupposes that the actors participating in the concertation have to negotiate to reach an agreement. The notion of consensus reflects a situation in which the final decision does not correspond exactly to the actors’ initial position, but that they nevertheless agree to since the decision results from a compromise between the participants. This compromise involves certain actors making concessions during the deliberations in order to reach a unanimous agreement.

After having studied the theoretical framework of concertation, the Board looked at how the authorities involved intended to implement concertation within the TGIRTs. The CNG and EIBJRG have both adopted operating rules for the TGIRTs on Category II and III lands. These rules basically reproduce the MFFP definition but also specify, notably: which actors are targeted to take part in the work; how the meetings are organized and run; how concertation occurs and how decisions are made. The rules also stipulate how minutes are produced and how participants’ satisfaction is measured, in addition to establishing a conflict resolution process.

It is important to mention that the operating rules for Category III land TGIRTs deviate from the theory by proposing decision-making by a 75%-majority vote when unanimity cannot be reached.

In the context of Chapter 3 of the Paix des Braves, concertation seeks to ensure that the concerns of Cree users and Jamesian users (on Category III lands) are taken into account in the context of forest management activity planning processes on the territory. To do so, these users are called to concertation, via the TGIRTs, in order to agree on local forest management objectives. The Board seeks to assess this mechanism’s effectiveness for promoting the Crees’ and Jamesians’ collaboration in determining common objectives and for integrating their concerns in final decisions related to forestry planning.

The rather open definition of concertation offers the possibility of defining flexible criteria based on more subjective indicators, such as satisfaction. Monitoring such a concept must focus on assessing the process first. Determining the criteria and indicators for monitoring objective 4 is based on the Chapter 3 TGIRT-related provisions, on existing official definitions and on the TGIRT operating rules as established by the authorities concerned.

[1] Ministère des Forêts, de la Faune et des Parcs. 2018. Guide de la table locale de gestion intégrée des ressources et du territoire : son rôle et son apport dans l’élaboration des plans d’aménagement forestier intégré.

CRITERION 4.1: PARTICIPATION AND REPRESENTATIVENESS AT TGIRTS (CAT. II AND III LANDS)

Concertation involves actors targeted by public authorities, in this case, more specifically the territory’s users–the Crees for Category II lands and the Crees and Jamesians concerned on Category III lands-who are invited to discuss and reach an agreement in order to set common goals. This criterion seeks to verify whether the actors provided for in the Paix des Braves are properly targeted by the delegate designation process, whether they are representative of their group within the TGIRTs and whether they are present at these panels. With this criterion, we are, therefore, more specifically interested in what happens before collaboration per se. We ask ourselves, which interest groups are invited? Is the delegate representative of his or her group? How are the invitations sent out? Who actually attends the meetings?

Related provisions

| C-4 s. 2 Goal and objectives of the establishment of TGIRTs Panel composition (parity) |

C-4 s.3 Prior consultation of interest group by delegate |

CRITERION 4.2: APPLICATION OF CONCERTATION IN THE TGIRTS (CAT. II AND III LANDS)

This criterion seeks to assess whether concertation actually occurs at the TGIRT meetings. It is important to ensure that, in addition to gathering around the same table, the users concerned by forest management activities on the territory actually have an opportunity to express their values, interests and concerns. We are referring to participation over and above physical presence that results from taking part in the discussions. We also need to look at how the decisions are made and how the consensus is determined. We must also validate whether the negotiations target the goals established at the outset, that is, to agree on local sustainable forest management objectives. Finally, since concertation can occur without arriving at a consensus, it is important to verify, in cases of disputes between delegates, whether the conflict resolution process is applied and whether the stakeholders concerned are satisfied with the outcome of the settlement.

Related provisions

C-4 s. 2. (a) and (b) Goal and objectives of TGIRTs

C-4 s. 6 Conflict resolution mechanism

CRITERION 4.3: CONSIDERATION OF TGIRT WORK IN FOREST PLANNING (CAT. II AND III LANDS)

According to the Paix des Braves, the main goal of the TGIRTs is to ensure that the concerns of the Crees (and Jamesians on Category III lands) are taken into account in the context of forest planning. Consequently, once the right people have been invited to the panel, have met, have held discussions and have agreed on common objectives, it has to be determined whether the TGIRTs’ work truly influences the decisions of the authorities responsible for forest planning. It may, in fact, happen that there is a consensus at the panel, without this consensus actually influencing the authorities’ decisions. If the content of the forest plans tabled by the authorities is not compatible with the interests and concerns of the stakeholders concerned or if a local forest management objective determined by the panel was not taken into account in the planning, the TGIRT in question can take recourse to a conflict resolution process. In this case, the Board will have to assess whether this process has been complied with and whether it satisfies the stakeholders concerned.

Related provisions

| C-4 s. 4 Content and preparation of PAFITs C-4 s. 6 Revision of PAFITs by the TGIRTs |

Conflict resolution mechanism C-4 s. 17 PAFIO deposit to TGIRTs |

INDICATORS AND VERIFIERS

Criteria 4.1: Participation and representativeness at TGIRTs (Category II and III lands)

- Delegate determination process

- Representation of group interests by the delegate

- Level of participation (attendance) by the Cree delegates

- Level of participation (attendance) by the Jamesians concerned (on Category III lands)

Criteria 4.2: Application of concertation in the TGIRTs (Category II and III lands)

- Involvement of Cree and non-Cree representatives in discussions

- Number of Cree and non- Cree concerns translated into Issues-Solutions*

- Level of understanding of panel files by the delegates

- Decision-making process

- Conflict occurrence

- Ratio of settled conflicts/conflicts in progress

- Level of satisfaction with the outcome of conflict resolution of the stakeholders concerned

Criteria 4.3: Consideration of TGIRT work in forest planning (Category II and III lands)

- Integration of Issues-Solutions* in the PAFITs

- Level of satisfaction of participants regarding their influence on decision-making

- Conflict occurrence

- Ratio of settled conflicts/conflicts in progress

- Level of satisfaction with the outcome of conflict resolution of the stakeholders concerned

- Respect for the conflict resolution process

- Respect of the PAFIO preparation process

For all indicators, the means of verification proposed are:

- Lists of TGIRT composition and appointed delegates

- Notice of meeting

- Meeting minutes

- Participation/attendance chart

- EIJBRG annual report on the TGIRTs

- Participant satisfaction survey

- TGIRT operating rules

- Observation of meeting dynamics

- Issues-Solutions* table

- Conflict monitoring chart/Conflict reports

- PAFIT local objectives section*The VOITs (value, objective, indicator, target) are now called Issues-Solutions by the MFFP